I

went overseas in July of 1943, just one of a group od about twenty-five G.I.s

who had been through a Military Intelligence training course in Camp Ritchie in

Maryland. Our great leader was Hans Mauksch, a PFC in this man's Army but an experienced

junior officer some years earlier in the Austrian army.

None

of us lacked for nerve so it wasn't surprising that we were able to talk ourselves

into the position of cadre, in charge of teaching certain subjects to the thousands

of G.I.s in the British Salisbury Plains staging area where we were located. The

subjects we taught were recognition of German uniforms, weapons and tactics, the

handling of their most common weapons and something about the Nazi psychology

that we were going to meet head-on in the not-too-distant future.

I

got elected to write the syllabus for each of those lectures, copies of which

I still have although they are on crumbling paper or in the form of mimeographed

pages. In any event, once I had finished that job, I was able to duck doing the

actual teaching and started to concentrate on the collection of German weapons.

They were to be found all over the place, having come in with the troops that

had already been through the North African campaign.

Pvt.

Ralph H. Baer (Serial No.32887607) in Tidworth

fatigues, field jacket, legging's

and all.

Our

training course was so successful that word got around. The press showed up one

day and interviewed us. A story, mostly about Mauksch, my buddy Decré and

me, appeared in YANK magazine, the Sunday edition of the army newspaper. Hans

Mauksch's picture was on the front page of the magazine and a very complimentary

story appeared inside. After that article appeared, MI Headquarters in London-located

at Eisenhower's European Theater HQ at Grosvenor Square-duly noted what we were

doing.

I

don't know how Hans pulled it off, but shortly after that article appeared, he

got a Second Lieutenant's commission. Additionally, from then on our group of

MIs immediately and officially reported organizationally to MI HQ in London. From

then on we took our orders from there. As a result, the local authorities' grip

on our destiny loosened considerably. We were almost in autonomous control of

our little organization! After all, London was not exactly next door. This was

the Army ??

*

Involuntary banishment to a Replacement Depot

In

May of 1944, I somehow got separated from my MI group; some orders got screwed

up and even Hans Mauksch couldn't get them countermanded in time to keep me from

being shipped off. Suddenly I found myself among a bunch of other GIs on the way

to a replacement depot somewhere in the south of England. It was the worst possible

place to be. I was unassigned, with no recent training of any kind-including weapons

firing-and I was destined to become a prime candidate for combat of some sort

in the near future.

The

weather was abominable. It rained constantly. There was foot-deep mud all over

the place. Duckboards were laid out in the company streets so you wouldn't sink

in past your ankles. Everyone was cold, damp and mostly miserable all the time.

We

were housed in old, single-story, British Army barracks that had a dirt floor

and a single, little potbelly, coal-fired stove at its center. In the morning

we would wake up covered with soot. Our GI blankets were black with coal dust

and so were our nostrils, mouths, faces and hands.

I

wasn't happy. I had left a secure and interesting job behind in exchange for waiting

to be shipped to the continent along with other, basically undertrained replacement

troops. Meanwhile, here I was, pulling night K.P. or guard duty. Once I "walked

a post" around a water tower on top of some god-forsaken hill in the middle

of the night, with my M-1 at right-shoulder arms in pitch-darkness! Like everyone

else around me, I looked ahead to an uncertain future amongst troops I did not

know. Rumors about the impending invasion of France set the scene.

One

night I was once again assigned to guard duty. I walked a post during the wee

hours of the early morning, criss-crossing the motor pool, supposedly guarding

the trucks parked there. A few lights on wooden poles barely illuminated the area.

All was quiet, nobody was out there in the damp and chilly night. About four in

the morning, with the first light of dawn breaking, I saw a guy in fatigues get

into one of the trucks. He idled the motor for a few minutes to warm it up and

then drove off. I thought about challenging him, but I wasn't really armed-I had

only an unloaded carbine and no ammo; besides, I had been given zip instructions

on what to do other than to "walk the post."

Later,

while I was off duty and sleeping on a cot in the guard's barracks, waiting for

my next shift, I was awakened by the Sergeant and the Officer of the Guard.

"What

happened to the truck?" they asked me.

"What

truck? Oh, the one that took off around four AM?"

"Yeah!

That one!"

The

truck had been stolen. I had visions of paying off that truck for the rest of

my life! Let's see...paying off five thousand dollars at five bucks a week would

take about forty years. I felt sick and started sweating out the impending disaster-like

being thrown in the brig!

Later

that morning, I was called in front of the camp commandant to explain what happened.

I told him that I had not received any orders to challenge anyone while walking

the post and that I had an unloaded rifle; and that in any event, we knew there

were troops leaving that morning so I thought nothing of having someone drive

a truck off the motor pool. He shook his head in disbelief at this display of

all-around stupidity but he dismissed me and that was the end of that. The truck

was later recovered somewhere in town. A British civilian had stolen it and taken

it for a joy ride.

Probably

the worst duty I had during those weeks at the Replacement Depot was night K.P.

during which I scoured the insides and the carbon-black outsides of GI garbage

cans from the canteen, working outdoors in nearly total darkness in the dead of

night. I came back to my barracks looking like a chimney-sweep.

When

I wasn't sleeping off guard duty or night K.P., or wasn't washing my clothes,

underwear, socks or my heavy GI overcoat in cold water, I sat outdoors during

every available daylight hour studying my algebra correspondence course. Like

everybody else's, my feet were constantly caked with mud, my leggings and socks

were soaking wet. We still had canvass leggings at that time. Paratrooper boots

with leather bindings a third of the way up the calf from the ankles hadn't been

issued yet, at least not to the regular ground troops. They came later. Naturally,

as if I had planned it, I caught pneumonia.

The

next thing I know it's morning, I'm on a stretcher, blood is trickling from my

nose. I'm feverish, and I'm being carried-along with my duffel bag-into an ambulance.

I was taken to a regular hospital occupied by the U.S. Army, somewhere to the

north. During my hospital stay I sat in bed between clean, dry, white sheets,

and studied my United States Armed Forces Institute (USAFI) Algebra II correspondence

course. I finished it there with grade of 97. Meanwhile the replacement troops

I had left behind were on alert; shortly after I had left them, they shipped off

to the Normandy beaches on D-Day, the 6th of June 1944.

Saved

by the bell and Algebra II! I didn't know then just how unbelievably lucky I had

been.

A

couple of weeks later, Hans Mauksch managed to get me back to Tidworth in the

Salisbury Plains and I was reunited with my MI group. Who knows how he pulled

that one off. Fortunately, Mauksch appreciated my contribution to the group and

wanted me back there-needed me, in fact. By now, I was the only member of the

group who knew every aspect of the large number of weapons that we toted around

with us. They were our most prominent calling card. That suited me fine.

Thank

goodness for Algebra 2. By the time we all moved on to France, things were not

nearly as hot there as they had been. I wonder whatever happen to the regenerative

radio receivers I built out of German mine detectors for the guys so they could

listen to Glen Miller and his band.

"I was more than a little lucky

to have Hans Mauksch come to my rescue once again. He sure had an uncanny way

of getting things done; his resourcefulness was impressive and those of us lucky

enough to be under his wing counted our blessings twice daily,

The

USAFI self-study Algebra Course and the cover of a USAFI brochure

The

gang in Tidworth (1944): From left to right:

Fred Decré, the Fischer

brothers, Yours truly (in fatigues) and Thoma

especially

when we stopped long enough to think about where we might otherwise be. His abilities

were also evident in later life. Hans eventually became a Ph.D. in philosophy

at the University of Chicago; unlike others with this pedigreed background, he

did not go on to teach philosophy to the next bunch of graduate students. Instead,

he revolutionized nursing education in this country. His wife, Inge, had an advanced

degree in nursing education and probably had something to do with his success.

Several teaching chairs in the nursing education community are named in honor

of Hans O. Mauksch.

While

the battles in France raged on, we remained in Tidworth, training troops on their

way over to the mainland. The war was next door but it seemed far away-how fortunate

we were! We had no idea, of course, how long our present situation would go on.

A

month or so later we moved on to France where some engineers had built a camp

on the grounds of what was once a Vanderbilt estate where Churchill would invite

himself to paint pictures during the years between the wars. I kept collecting

European small arms and set up a fairly impressive exhibit. We also taught the

troops how to fire some of these weapons. After the war was over, I had eighteen

tons of that stuff and had it crated in an ordnance depot in Paris for shipment

back to the good old USA in January of 1946. There we set up small arms exhibits

at Aberdeen, Md. Proving Grounds, at Fort Riley, Kansas and at the Springfield,

Mass. armory....whereupon I quit the Service, went back to school to get an engineering

degree in radio and television.

Playing Interactive Video War Games

All

of my experience with small arms and larger weapons had a videogame-related sequel.

After the war, I became a TV Engineer and moved up the ladder from engineer to

VP for engineering running ever larger organizations. While at Sanders Associates

in the mid-sixties I came up with the concept of home videogames. Not too many

years later, when VCR's were readily available, I demonstrated "shooting"

at Russina tanks moving by on a 60 inch TV projection screen, using a converted

LAW (Light Anti-Tank Weapon). The latter was, in effect, a precision optical gun

that could resolve a short line segment of the TV picture's raster and tell the

associated computer just where the LAW's optics were pointing. Pulling the trigger

resulted in a computer-generated graphic of an explosion at the exact place at

which the LAW was aimed.

That

demonstration resulted in a succession of videogame-like weapons simulation and

training contracts for the company which got progressively more complex.

A

photo of our electro-optic LAW is shown below.

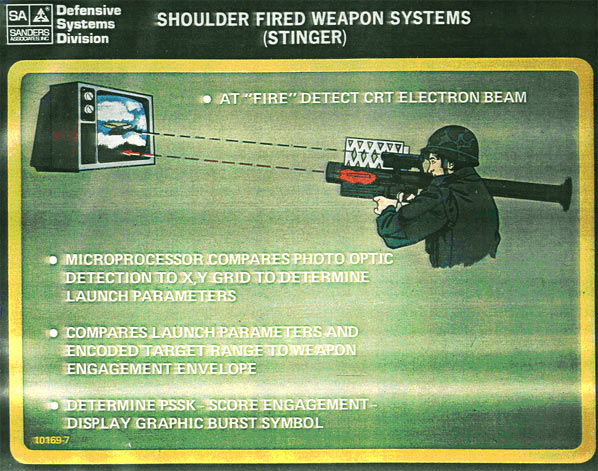

Another

typical example of 1970's and 1980's weapons training and simulation work using

video game technology was the Stinger Missile system shown below:

Twenty

years later, videogames have become an integral part of US Army training and recruiting.

Been

there, done that...

Read

other Ralph Baer Articles:

The

Coleco Story

My

Trip to Meet Ralph Baer

Japanese

Science Museum Features Videogame History

E-Mail

to order

a copy of this fantastic book

ONLY

$29.99